The Role of Serenade

A year ago I asked myself the question, “why do dancers dance?” And I thought “well, dancers dance because they want to perform good, exciting, and fulfilling choreography.”

That question also prompted me to consider George Balanchine’s Serenade. For years I’ve listened, read, and watched multiple generations of dancers discuss this ballet in a way that I’ve never heard other pieces of choreography described before: like a spiritual experience. Ask any dancer, critic, or admirer of the art form and they will tell you that Serenade is magical. Serenade was even the first ballet New York City Ballet chose to premier after the Covid-19 pandemic. There’s so much history wrapped up in this 33 minute ballet. Moments such as a dancer coming late to rehearsal or falling during a run through have been choreographed into the work. And I admit, I find those moments of process being incorporated into the choreographic product fascinating. Yet, after researching Balanchine, The School of American Ballet (SAB), and New York City Ballet (NYCB), it became overwhelmingly evident that dancers would continuously put themselves in harm's way to please Balanchine; even to this day, more 40 years after his death, dancers continue this practice just to be awarded the chance to perform in his work.

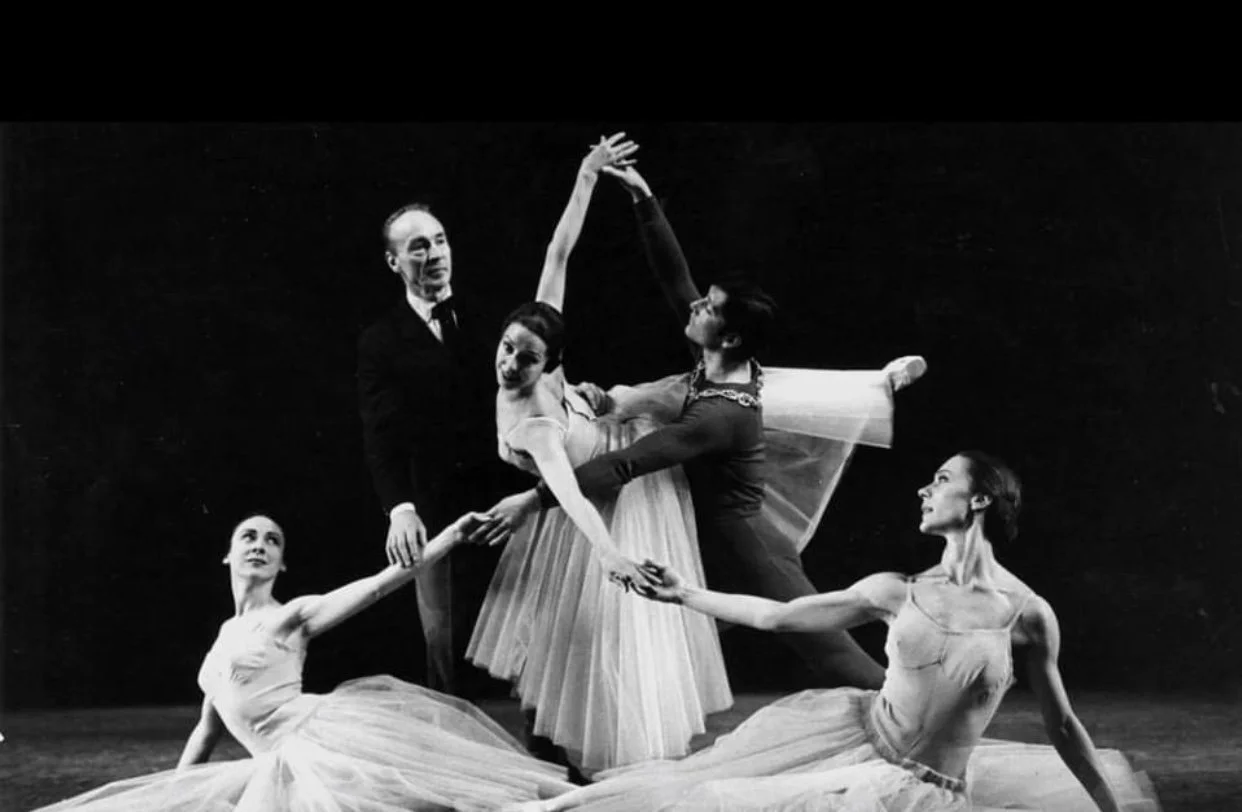

Balanchine staging Serenade at the Royal Ballet 1964

Photographer unknown

Serenade, NYCB 2016

Photo by Paul Kolnik

At first glance, Serenade seems to be a celebration of women. Admiring them, their beauty, and what they can do as athletes and artists. However, from my perspective, as the work goes on, the inclusion of men skews this viewpoint. The ballet is made up of a corps de ballet of 22 traditionally female dancers, 3 female soloists (referred to as the Russian Girl, the Waltz Girl, and the Dark Angel), and 3 male dancers that appear almost exclusively to partner the women. Even the use of language “The Russian Girl”, “The Waltz Girl” clearly displays the constant infantilization of women in classical ballet. Femme adult ballet dancers are typically referred to as “girls” despite their age and experience, and this is mirrored in their expectation to maintain a physique that resembles a prepubescent child.

I’m not trying to tear down this work; I can admire the beauty of Serenade. However, is this ballet worth the suffering that dancers inflict upon themselves due to pressures from the people who hold power within the ballet industry? Are aesthetics ethical? And do dancers and audience members prefer destructive leadership strategies in order to create “better” balletic work?

What’s in a color? #363: Balanchine Blue

Serenade, NYCB 2021

Photo by Erin Baiano

Balanchine Blue is actually not just one blue, it’s many different shades depending on which ballet you’re looking at. The colors especially shifted in the later Balanchine works as his eyesight worsened and his perception of color distorted.

#363 was the gel I put in the cyc to give us access to a true, cerulean, Balanchine Blue. It was incredibly important to me that this color was as accurate as possible.

The lighting served several purposes. I chose to highlight the significance of multiple shades of blue again when the dancers mimed the opening of Serenade in Act 4. Although the costumes we created were black tutus, the original Serenade tutus were a light blue shade. I chose to bring the original costume colors back into the palette by using LED lights to achieve the exact color. Serenade opens with the corps de ballet with hands outstretched in the air. This famous position came to be due to a dancer blocking sunlight from her eyes; the placement of the LED lights in This is Ballet served to simulate the sun from that day in Balanchine’s rehearsal when the ballet was created.

For more detailed explanations and theories on Balanchine Blue I invite you to take a look at this New York Times article written for the 75th anniversary of New York City Ballet.

Choreographic References to Serenade

The opening moments of Serenade are the most recognized of this ballet. I felt it was imperative to include that moment in This is Ballet. If you’re familiar with Serenade, the first image that comes to mind is the opening formation with the dancers’ hands in the air. This is another moment of process absorbed into the ballet because during Balanchine’s rehearsal a dancer held her hand up just like that to shield her eyes from the sunlight pouring in through the window, which was then kept and staged as the opening of the entire work. This unison moment is beautiful and holds power. However, I think it becomes all too easy to forget what women have gone through just to look “pretty” on stage. The opening of Serenade starts with a more human-like stance. They are not turned out, their arms are not in a balletic position. They’re simply standing there, feet together, right hands in the air. Slowly, the dancers begin to move their arm and after a few moments, round their arms, open their feet to first position, tendu to 5th, and they are ready to start the ballet. This moment represents their transformation from people into dancers.

In my version, I placed their right arms slightly higher than Balanchine’s to be more in line with where the light was coming from. You’ll also notice the dancers start in first position instead of parallel (sometimes referred to as 6th position) and rounded arms. This is not a mistake. I made this choice because after echoing the beginning moments, the dancers smear their hands across their mouths, look at the audience confronting them, and then instead of transforming into ballet dancers they close their feet to parallel, then relax their arms, reinforcing their identities as people instead of dancers.

The changing 3rd arabesque port de bras is also an iconic moment from Serenade.

In my version, I was interested in using that choreography against the power structure that gave it life. It’s used as a means to chase the male artistic director figure off stage enabling the women to reclaim their power.

Another discernible moment in Serenade is when 3 soloist dancers take their hair down during the ballet. You don’t really notice it until their hair is already down. For the first soloist (The Waltz Girl) it’s hidden in a series of chaîné turns as she uncoils her hair and the other two simply change theirs backstage.

In This is Ballet, after moments of exhaustion (a reality we’re not allowed to show on the ballet stage) the dancers begin removing the pins from their hair. This serves not only as a reference to Serenade, but as a vehicle for autonomy, agency, and rebellion against the prescribed uniform often required of them.

Other moments referencing Serenade during

Act 4: “This is Power”

As mentioned previously, my goal is not to vilify or cancel Balanchine. I even resonate with some of his practices like creating choreography for specific dancers or modifying existing choreography to better suit new individuals. In comparison to his successor (Peter Martins) he was not an overtly aggressive leader. Still, that does not absolve him from responsibility or the fact dancers put themselves in harm's way just to dance for him. Evidently, he still had a means of obtaining what he wanted. All of this to say, I don’t believe we should stop performing his work. As a community we just need to remember everything that surrounds the creation of it.

If we cancel him and his ballets, we are not only erasing some very beautiful choreographic work, but forgetting all of the women that went through so much to uphold and carry these ballets. I don’t think it’s fair to them to diminish what their contributions were. In an industry that women dominate but men rule, it’s necessary to acknowledge the contributions of women.

Performance Videos: Samuel Sierra

Performance Photo Thumbnails: Zoe Knowles